Chapter 2: The COVID-19 pandemic

Impact of COVID-19 on mental health

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was important for governments to understand not just the health impacts of the virus itself but the economic and mental health impacts for the whole population, particularly vulnerable groups. This understanding supported governments both to respond to the short-term impact of COVID-19 and to ensure that longer-term consequences were addressed and planned for. National data agencies adopted a number of measures to provide rapid data, including:

- • flexible approaches to collecting and analysing data within existing data collections to ensure that they were responsive to the needs of decision makers

- • establishing collaborations with each other and with mental health researchers to ensure that coordinated information was produced in a timely fashion

- • providing the Australian Government with weekly updates on Australia’s mental health and use of mental health services, including use of crisis helplines

- • establishing new data collections to measure the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated restrictions on Australian households • establishment by Australian mental health and suicide prevention researchers of platforms to track and share research protocols, measures and results for COVID-19-focused research, in an effort to minimise duplicated effort and produce the strongest possible research.

The Australian Government announced $2.4 million for collection of up-to-date evidence and modelling of the mental health impacts of COVID-19. Box 10 gives an overview of COVID-19 mental health–related data in Australia.

Box 10: Sources of COVID-19 mental health–related data

The Commission prefers data that is nationally representative, with appropriate sample sizes and statistical power. While other data sources may have interesting findings, we are unable to make statements about the general Australian population from data that is not nationally representative or has sample bias. Together, the following sources of information provide a national picture of the impacts of COVID-19 on mental health.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Household Impact on COVID-19 Rapid Surveys

This multi-wave survey provides insights into the prevalence and nature of impacts from COVID-19 on households. The ABS Rapid Survey was conducted fortnightly until August 2020, and now monthly, and is based on a random sample of 1,000–3,400 households with an adult aged 18 years or over.

Australian National University (ANU) Monitoring the Impacts of COVID-19 (ANU Poll)

A COVID-19 impact monitoring survey held in April, May, August and October, including mental health–related questions, was developed by the ANU Centre for Social Research & Methods. It uses a longitudinal sample of 2,500–3,000 people aged 18 years and over from the Life in Australia panel.

Melbourne Institute (University of Melbourne) Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey

This survey provides insights on how Australians are adapting to various changes in Australian, state and territory government policies as the pandemic evolves. It asks about feelings of depression or anxiety as a measure of general mental distress, rather than attempting to measure mental illness. On a weekly basis, 1,200 people aged 18 years and over are surveyed.

Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll

This survey was conducted in June 2020 and asked Australian parents about the health behaviours of their children and themselves in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey included questions about lifestyle, mental health, the use of health services and family finances. This was a one-off online survey of 2,018 parents.

The Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll is an ongoing survey whose topic changes from poll to poll.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) COVID-19 Monitor survey

The purpose of this multi-wave survey was to reveal how people were feeling during the COVID-19 lockdown and provide insights into what Australians think about governments’ responses to the pandemic. A total of 2,297 participated in this survey.

Digging Deeper: Exploring the Effects of Coronavirus project

The Commission engaged the ANU National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health to review findings of pandemic research in Australia and compare them with international data, and data from previous pandemics and disasters. The research, which is due to be completed in mid-2021, is exploring the effects of quarantine and self-isolation on people’s mental health. It will dig deeper into people’s experiences through qualitative interviews.

Other key sources of information for impacts of COVID-19 on mental health

The longer-term mental health impacts of COVID-19 are being explored through a range of studies and research. The Open Science Framework, run by the Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use and ANU, has collected information on a number of Australian studies on mental health and COVID-19 with a view to collaboration and data sharing.

The mental health impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be unevenly experienced because they are affected by individual social and economic circumstances.109 Many researchers have collected evidence since February 2020 to better understand how the direct experiences of COVID-19, such as social isolation, loss of employment, concern about contracting COVID-19 (or loved ones contracting COVID-19), or major disadvantage due to COVID-19 restrictions, have impacted the mental health of people in Australia. To date, more than 100 mental health–related research studies on COVID-19 have been initiated. With Australia officially entering an economic recession in September 2020, based on past experiences, it is expected that the associated job losses, mortgage pressure, house repossessions and relationship stress will impact longer term on the mental health of many Australians. A number of economic measures have been introduced, both nationally and at the state and territory level, to financially assist businesses and individuals during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Economic and health concerns

From the outset of the pandemic, it was evident that not only would the national economy be impacted by the massive disruption to usual economic functioning, but that communities, families and individuals would be directly impacted. Estimates by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) indicate that almost 2.7 million people were affected by either losing their job in the first two months of the pandemic in Australia (April and May 2020) or working significantly reduced hours. The official unemployment rate reached 7.5% in July 2020 and dropped in the next month to 6.8%. An additional 3.5 million people were assisted through the Australian Government’s JobKeeper program, which generally meant receiving a reduced income; however, it maintained a crucial employment connection. Others worked reduced hours, with underemployment reaching a high of 13.7% in April 2020 and decreasing to 11.2% in July 2020.

The impact on people’s daily lives was varied as work, school and home life merged in an unprecedented way, affecting all in our communities—millions were adjusting to working from home, often at the same time as their children were studying from home. Other workers such as essential services were being pushed to their limits, with longer work hours, higher demands and an increased threat to their own health.

At the end of July 2020, 77% of those surveyed in the Melbourne Institute’s Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey indicated that they would prefer to stay at home to minimise the risk of infection than continue with usual activities. The surveys, conducted each week, also indicated an increasing vulnerability to mental illness and a higher level of pessimism about the longer-term impacts of COVID-19.

Social isolation, loneliness and mental distress

During COVID-19, many people have struggled with fear and uncertainty about their own health and that of their loved ones to varying degrees.

In addition, increased social isolation and loneliness is a major adverse consequence of COVID-19, and is strongly associated with anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide attempts across the lifespan.

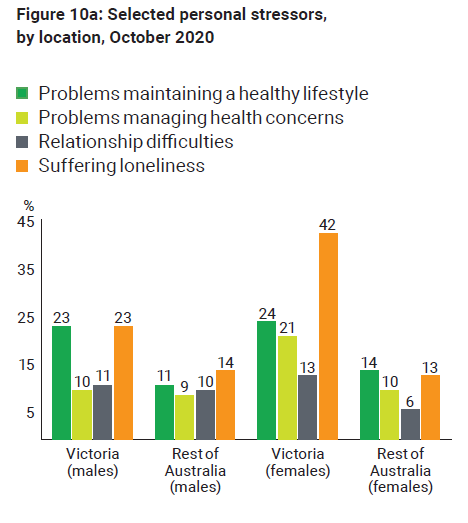

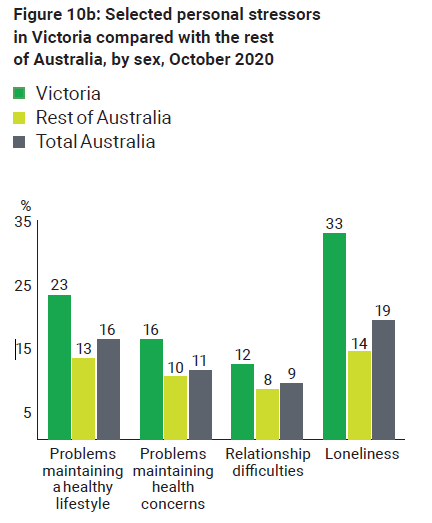

Around 1 in 5 people across Australia in an October survey by the ABS reported experiencing loneliness (Figure 10a). Significantly higher rates (33%) of loneliness were reported by Victorians compared with other locations, especially by Victorian women (42%).

Figure 10a: Selected personal stressors, by location, October 2020

Figure 10b: Selected personal stressors in Victoria compared with the rest of Australia, by sex, October 2020

Source: ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, October 2020

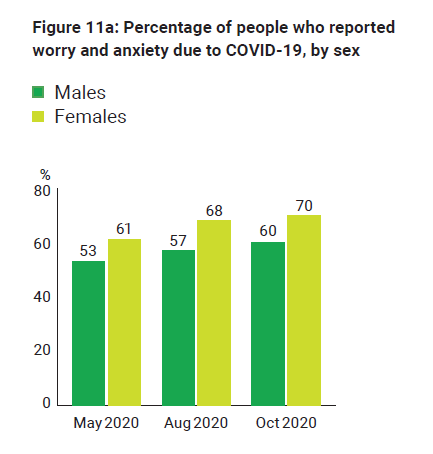

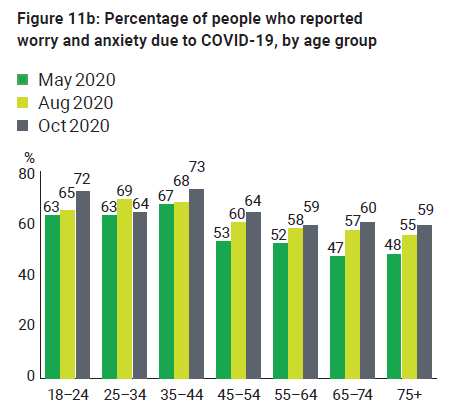

An Australian National University (ANU) study found that, in May, August and October, females had higher levels of anxiety and worry about COVID-19 than males, and younger people had higher levels than older people (see Figures 11a and 11b).

According to the Melbourne Institute’s Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey, 15–21% of people reported feeling depressed or anxious most of the time from May to October. The proportion of people who felt anxious or depressed most of the time in October varied by state. During mid-October, Victoria had the highest proportion (27%), followed by South Australia (26%), Queensland (20%), Western Australia (20%) and New South Wales (19%). This survey asks about feelings of depression or anxiety as a measure of general mental distress, rather than an attempt to measure mental illness.

Figure 11a: Percentage of people who reported worry and anxiety due to COVID-19, by sex

Figure 11b: Percentage of people who reported worry and anxiety due to COVID-19, by age group

Domestic violence

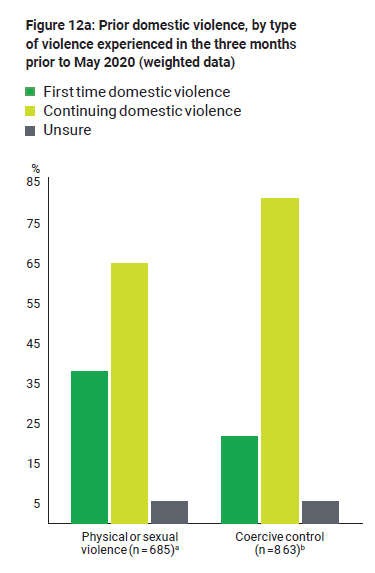

For many, the pandemic coincided with the onset or escalation of violence and abuse. Social isolation and lockdowns can compound this situation, by reducing access to support services for victims of domestic violence, child abuse and neglect; as well, increased financial insecurity limits accommodation options. By late March 2020, Google searches for domestic violence help were at the highest level in five years, with an increase of 75%. A survey by the Australian Institute of Criminology also revealed that, of those women who reported experiencing domestic violence in the three months before the survey, one in three said this was the first time their partner had been violent towards them.

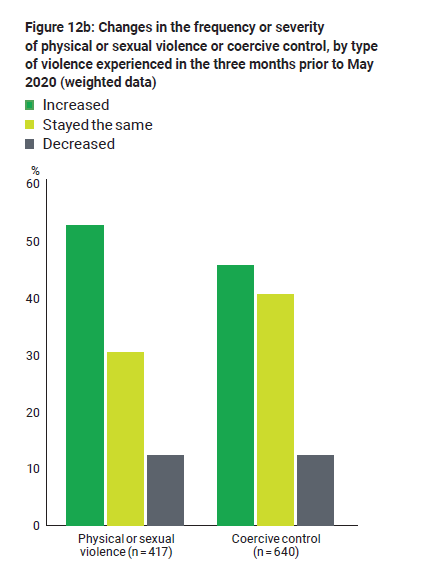

For women who had experienced physical or sexual violence before the COVID-19 crisis, more than half said the violence had become more frequent or severe since the start of the pandemic (from February to April 2020) (see Figures 12a and 12b).

Although a significant proportion (two-thirds) of women did seek help from police, government agencies, or nongovernment agencies and informal sources, many were unable to because of safety concerns. This is consistent with the concerns raised by many in the domestic violence sector that they found it difficult to engage with women during the periods of lockdowns. It also helps to explain why the number of domestic violence incidents reported to police has not increased.

In March 2020, the Australian Government announced a $150 million domestic violence emergency response package. Of this, $130 million will go to states and territories to strengthen family and domestic violence support services and accommodation options. An additional $3 million was announced in July to provide more counselling and support services for women and their children who have experienced family violence.

A national parliamentary inquiry into family, domestic and sexual violence was announced in June 2020. This included an investigation into the impact of natural disasters and other significant events such as COVID-19, including health requirements such as staying at home, on the prevalence of domestic violence and provision of support services. This inquiry will inform the next National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children.

Figure 12a: Prior domestic violence, by type of violence experiences in the past three months (weighted data) (%)

Note: Limited to women who were in a cohabiting relationship and reported that they had experienced domestic violence in the three months prior to the survey. Percentages may not total 100 due to rounding of weighted figures.

- a: Total includes 41 women who were unsure whether they had experienced physical or sexual violence prior to February 2020

- b: Total includes 51 women who were unsure whether they had experiences emotionally abusive, harassing or controlling behaviour prior to February 2020

Figure 12b: Changes in the frequency or severity of physical or sexual violence or coercive control, by type of violence experienced in the past three months (weighted data) (%)

Note: Limited to women who were in a cohabiting relationship in the past 12 months, had experienced domestic violence in the three months prior to the survey and had experienced violence or abuse from their partner prior to February 2020. Respondents could report experiencing both physical or sexual violence and coercive control.

Use of substances, alcohol and other drugs, and gambling

The significant changes to daily living due to the pandemic affected substance use in varied ways (noting that not all substance use is considered problematic). As part of the population health response to COVID-19, we need to monitor patterns of substance use (including alcohol and other drugs) associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, because substance use is a risk factor for mental ill-health and may exacerbate existing mental illness.

An increase in alcohol consumption during the lockdown period is evident for both males and females. A study released by the ANU in June 2020 showed that the main reason for increased drinking in both males (67.3%) and females (63.7%) was more time at home. However, increased stress was the second biggest driver for females (41.9%) and boredom for males (49%).

To understand any changes to drug use due to the pandemic, the Australians’ Drug Use: Adapting to Pandemic Threats (ADAPT) Study surveyed those who used illicit drugs on a monthly basis in 2019, and compared their previous use to use in the first few months of the pandemic. The responses were specific to drug type and did not seem to address whether access to specific drugs affected patterns of use:

- • More than half (56%) of respondents reported an increase in cannabis use, while 15% reported a decrease.

- • Around 2 in 5 (43%) reported an increase in alcohol consumption, one-third reported a decrease, and 1 in 4 said it was stable.

- • Almost half of people who used MDMA reported a decrease in use; likewise for people who used cocaine (39%) and ketamine (42%).

- • More than half who used pharmaceutical opioids, benzodiazepines and gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) reported that their use was stable (56%, 53% and 50%, respectively).

- • Only 4% had accessed drug treatment, and 2% reported they had tried but were unable to access drug treatment, in the previous four weeks.

As part of its pandemic response package, the Australian Government provided funding to a range of services to provide online and telephone services for people affected by substance use. These services play an important role in counselling services and were even more essential when face-to-face counselling was limited during lockdowns.

Evidence on changes to gambling practices during the pandemic indicated some increased activity, especially among young men. The Gambling in Australia during COVID-19 survey collected information from more than 2,000 people who gambled. It indicated that the number of survey participants who gambled four or more times a week increased from 23% to 32% during June–July 2020. The biggest spike in frequency and monthly gambling spend was seen in young men aged 18–34 years, increasing from a median of $687 to $1,075. This group was also most likely to sign up for new online gambling accounts, making up 79% of new account holders.

Suicide and suicidal behaviours

Despite concern about a possible increase in suicides due to increased risk factors related to COVID-19, available data suggests that, as of September 2020, there has not been an increase in suicide deaths.

A significant increase since COVID-19 in the use of mental health services and an increase in psychological distress reported, particularly among young people, is evident from data from the new National Suicide and Self-harm Monitoring System (see Section 1, Chapter 2).

In the recent State of the nation report by Suicide Prevention Australia, people were asked to nominate what they thought would be the greatest risk to suicide rates over the next 12 months. Social isolation and unemployment were seen as the highest risk. The report provides insight from suicide prevention support providers on the current situation in the sector. Nearly 80% of respondents said they had seen an increase in demand across all support services in the past 12 months. Many services reported a shift to online services during the COVID-19 restrictions, which increased the reach of online platforms.

Governments have responded to COVID-19 pandemic concerns by announcing a range of initiatives aimed at reducing suicide risk and improving suicide prevention systems; these are outlined in Appendix 2. Further work is anticipated from the release of the final report from the National Suicide Prevention Adviser.

Impacts of reimposition of restrictions

Victoria experienced a second wave of COVID-19 over five months from June to October 2020, peaking in August. Research has indicated that longer periods of quarantine and social isolation can be associated with worse mental health outcomes. In the four weeks to 11 October, numbers of people accessing items under the MBS Better Access initiative were 31% higher in Victoria than in the rest of Australia. Various mental health helplines also experienced increased use during this time, including the Beyond Blue Coronavirus Mental Wellbeing Support Service, Lifeline and Kids Helpline.

In August 2020, as part of the Australian Government $31.9 million announcement, 15 mental health clinics, called HeadtoHelp, were created across Victoria to further enhance essential support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Victorian Government provided $59.7 million to support these clinics, by boosting the capacity of clinical and community mental health services. The clinics opened on 14 September, primarily targeting mild to moderate mental health issues. They are located at various GP clinics and community centres, where health care is generally accessed. The HeadtoHelp model of care was co-designed with Primary Health Networks (PHNs), the Australian Government and the Victorian Government. Funding is committed to monitor and evaluate this new model, so that we can learn from the implementation and operation of this surge capacity response to the pandemic.

Further restrictions were declared in Adelaide and the Northern Beaches, New South Wales, in the later part of the year. On 18 December 2020, the Northern Beaches local government area of Sydney was declared a COVID hotspot due to discovery of a cluster of cases in the suburb of Avalon, resulting in new restrictions and border controls for people living in this area and eventually Greater Sydney.

National response

Public mental health messaging

Across the sector, it was recognised that a universal public mental health strategy was required to reach the whole population, as everyone was affected by the pandemic to some extent.

The Commission collaborated with mental health organisations, experts and leaders across the country to develop and launch #InThisTogether—a national online campaign with evidence-based practical mental health and wellbeing tips.

Six months on, research confirmed the impacts of pandemic lockdowns and restrictions on at-risk groups and the broader community, and a further stage of this campaign was launched in August 2020.

#GettingThroughThisTogether built on the success of #InThisTogether, acknowledging the continuing challenges for many people, as we navigate the compounding impacts of the pandemic. Ten new practical tips were made accessible online; these were developed in collaboration with more than 20 mental health and social service organisations to help everyone to get through these extraordinary times. In addition, Head to Health, the digital mental health platform, has a dedicated page updated regularly for COVID-19 with mental health tips, resources and support services.

National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan

On 15 May 2020, National Cabinet endorsed the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan as a response to the national public health emergency. The plan was based on stakeholder consultations, which received approximately 102 submissions of feedback, advice, commentary or revision from 75 stakeholders representing government, nongovernment organisations and individuals. The plan was developed under the co-leadership of Victoria, New South Wales and the Commission and has been informed by all governments. All jurisdictions agreed to provide funding and implement the plan’s actions. The Australian Government committed $48.1 million to support the plan.

The plan includes priorities for both the response and recovery periods, with flexibility for jurisdictions to respond to the needs of different communities. The plan identified three areas in which all jurisdictions could immediately act to fundamentally alter the trajectory of mental health impacts of COVID-19 and limit adverse downstream outcomes:

- • data and modelling—immediate monitoring and modelling of the mental health impact of COVID-19

- • outreach—adapting models of care to changing sites of service delivery

- • connectivity—improving service linkage and coordination.

The plan is a testament to a unified commitment, by governments and the sector, to support all Australians’ mental health and wellbeing during the response to, and recovery from, the COVID-19 pandemic. The plan reflects the need for timely data to inform suicide prevention responses through one of its three priority commitments.

The Commission is monitoring and analysing information on proposed and announced actions and programs that address the immediate actions and priority areas of the plan.

Mentally healthy workplaces during COVID-19

The Commission, in conjunction with the Mentally Healthy Workplace Alliance, has recently released a series of evidence-based, easy-to-use guides to support the mental health and wellbeing of Australian workers and to encourage mentally healthy workplaces during COVID-19.

These guides have been created by experts to provide practical tips and advice on helping employers and employees to look out for the signs that someone may need support, and assist them to find help when they need it. Resources have been developed for sole traders, small business, and medium to large business.

The National Workplace Initiative (NWI) provides a nationally consistent approach to workplace mental health (see Box 11). Although the NWI is managed by the Commission, the Mentally Healthy Workplace Alliance continues to guide the NWI and provide expert advice on its implementation.

Box 11: The National Workplace Initiative

The National Workplace Initiative (NWI) aims to help bring about national consistency in how organisations and workplaces support their employees. It aims to create an evidence-based framework for creating mentally healthy workplaces; connect organisations to the right resources via a digital platform; amplify and strengthen exemplar programs already underway; and highlight gaps in research, resources or services.

The Australian Government provided $11.5 million over four years in the 2019–20 Budget to deliver the NWI, which is being developed with input and guidance from a wide range of stakeholders. Having acquired an understanding of the challenges facing business, the Commission is now working to identify solutions that will support organisations in creating mentally healthy workplaces. The first version of the NWI digital platform, and a roadmap for how this will grow and expand over time, is expected to be available in 2021.

Mental health items under the Medicare Benefits Schedule

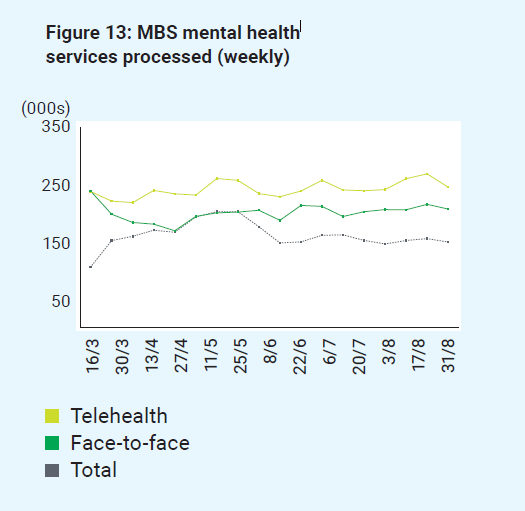

COVID-19 has led to substantial changes in the delivery of mental health services, most notably an expansion and increase in use of telehealth and digital health services. There was a significant uptake in the use of telehealth and digital health services during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Box 12 for usage data by service).

The announcement of new MBS telehealth items to help reduce the risk of community transmission of COVID-19, and provide protection for patients and healthcare providers, was welcomed by the mental health sector. These MBS telehealth items were initially available, until September 2020, to a range of health services, including clinical psychologists, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. In November 2020, with more than 40 million telehealth consultations since March 2020, the Australian Government announced its intention to make telehealth an enduring feature of Australia’s health system and will work with the sector to co-design what this will look like.

On 2 August 2020, the Australian Government announced an additional 10 subsidised psychological therapy sessions for people affected by restrictions in areas impacted by the second round of COVID-19 lockdowns. In the 2020–21 Budget, the Australian Government announced the extension of this measure nationwide under the MBS Better Access initiative.

Telehealth items provided safe options for people—particularly those with chronic health concerns—to continue to access mental health services. A significant increase in telehealth consultations over face-to-face sessions was seen (see Box 12). During the peak of the pandemic, Australia-wide telehealth MBS Better Access items were being accessed by nearly 50% of people using the services. By October, nearly two-thirds of services had returned to being delivered face to face.

Box 12: Data on use of telehealth and digital health services

Note: Direct comparisons between organisations are not appropriate because of differences in populations being serviced, service models, funding envelopes, workforce availability and information systems. Comparisons with 2019 should be made with caution because historical trends may be affected by a range of events, including planned awareness-raising campaigns.

Figure 13: MBS mental health services processed

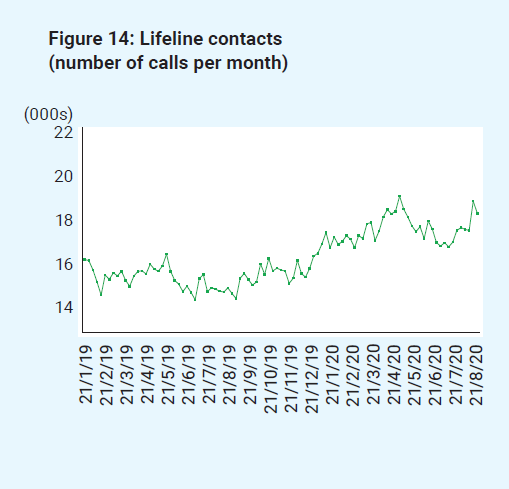

Figure 14: Lifeline contacts

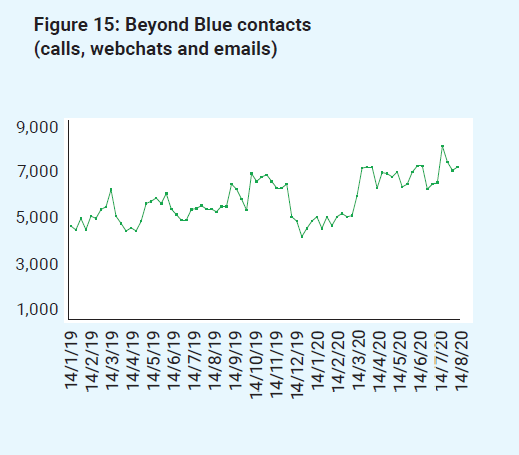

Figure 15: Beyond Blue contacts (calls, webchats and emails)

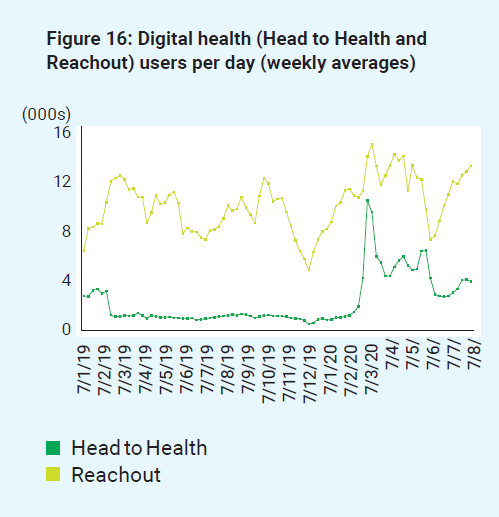

Figure 16: Digital health (Head to Health and Reachout)

Responses to specific impacts on diverse population groups

Although the events of 2020 have affected all people Australia-wide, some groups are more vulnerable to the economic, social, physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 as a result of pre-existing inequities in access to health care, housing, income and social supports. Responses by governments need to target the specific needs of particular population groups, because how they respond to the impacts of the pandemic will be influenced by their own experiences of a range of adverse social, economic and health outcomes, including homelessness, unemployment and incarceration.

Older people

From the outset of the pandemic, older people, whether living in the community or in an aged care facility, were identified as the most at-risk population. The risk of severe illness from COVID-19 increases with age; people aged over 60 years are at high risk. Some chronic medical conditions that are more prevalent in old age weaken the immune system, thereby increasing the risk. Older people are especially vulnerable to respiratory diseases.

Anxiety for older people may also have been increased by regular media reports detailing a higher rate of infection and mortality among older people. Lower digital literacy of some older people, lower access to technology and issues such as hearing loss have meant that digital avenues commonly used to mitigate social isolation have been less accessible for older people. This is reflected in the Families in Australia study conducted by the Australian Institute of Family Studies. People over the age of 70 reported having significantly less contact with family during the pandemic. Only 23% of people aged over 70 reported having daily contact with family living elsewhere, compared with 40% of people aged under 40.

Older people living in aged care facilities were disproportionately affected by COVID-19. As at 23 October 2020, more than 2,000 COVID-19 cases had been reported in residential aged care facilities. A total of 904 deaths as a result of COVID-19 had been reported, of which 682 were people living in residential aged care facilities, mostly in Victoria. The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Aged Care Royal Commission) noted that COVID-19 was the greatest challenge experienced by the aged care sector in Australia, with the pandemic exposing systemic weaknesses in the system.

The Aged Care Royal Commission launched an investigation of the response to COVID-19 in aged care. Expert witnesses during the investigation pointed to the fundamentally flawed approach of treating aged care and health care, including mental health care, as two separate industries.

The COVID-19 crisis in aged care highlighted the need for better collaboration and communications between the health (and mental health) system (especially hospitals, general practice and ambulances) and aged care. In late July 2020, a collaborative approach was implemented jointly by the Australian and Victorian governments with the formation of the Victorian Aged Care Response Centre, which has set a national standard for the delivery of emergency support.

Although many residents of aged care facilities have not experienced a COVID-19 outbreak at their facility, they have endured social restrictions for most of 2020 that go beyond those of the general community.

The Aged Care Royal Commission’s COVID-19 hearing, conducted in August 2020, considered the balance between managing risks posed by a future pandemic or infectious disease outbreak and the importance of mental health, wellbeing and quality of life of aged care residents. Family and friends shared with the Aged Care Royal Commission the profound impact of visitation restrictions, as visits have an integral role in care and support for residents.

Based on its findings, the Aged Care Royal Commission recommended that the Australian Government provide funding to people in aged care during the pandemic. This recommendation included ensuring adequate staff to allow continued visits, and allowing for the creation of MBS items to increase access to allied health professions, including mental health services. The Australian Government accepted all six recommendations made by the Aged Care Royal Commission, including implementing measures to support mental health care for residents.

In May 2020, the Australian Government announced a $6 million package intended to prevent loneliness and isolation in senior Australians. This included almost $5 million to significantly expand Friend Line, a national telephone support service for older Australians. It also included $1 million in grants to 215 local community organisations to provide at-risk seniors with digital devices such as mobile phones and laptops.

The Australian Government has also allocated $19 million under the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan for PHNs to commission additional mental health nursing services or equivalent support for older people who are experiencing social isolation or loneliness as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Services will be available for 12 months to people aged over 65 who live in residential aged care facilities or in the community.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities experience some of the worst health outcomes worldwide. This is often due to existing health inequities such as a high burden of chronic disease, poor nutrition, overcrowding, systemic racism and poor socioeconomic situations. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are at heightened risk of mortality from COVID-19 compared with non-Indigenous people. However, in comparison with the devastating incidence of COVID-19 in Indigenous communities abroad, the number of COVID-19 cases among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is six times lower than if the population were affected at the same rate as the rest of Australia.

The low proportion of COVID-19 cases in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been attributed to the swift health response from the Aboriginal community-controlled health sector, led by the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and other peak organisations.

In response to the pandemic, NACCHO called for protection and support in restricting access to rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, to reduce the risk of contact with nonresidents. Local planning was led and informed by the local needs and requirements of local communities, with an assessment of the need for rapid employment of additional health workers, and access to physical infrastructure to enable quarantine of COVID-19 patients. This response protected and prepared communities for lockdown, developed local communication strategies, and united diverse sectors such as health, education, land councils and government agencies.

People living with mental illness

People with a pre-existing mental illness are particularly at risk of severe impacts on their mental health as a result of COVID-19. In addition, the COVID-19 emergency has the potential to increase the number of avoidable deaths of people living with mental illness. Already, people living with mental illness have significantly higher prevalence of preventable physical diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases and cancer, and are particularly vulnerable to morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19.

Evidence suggests that people living with mental illness are more likely to be affected by emotional reactions to COVID‐19. This can exacerbate symptoms of mental illness or cause relapse, thereby worsening conditions and increasing the risk of delayed diagnosis and treatment of other conditions, including highly infectious diseases such as COVID-19.

Disruptions in mental health care and supports due to physical distancing restrictions may contribute to worsening mental health, because not everyone has access to online and telehealth services. Data indicated that some people living with mental illness were disconnecting from services in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consumers responding to a survey by the New South Wales lived experience peak group, BEING, in April 2020, reported the negative impact on their mental health of the loss of their support worker visits. They also reported that trips to the shops required them not just to be responsible for their own emotions but to deal with heightened emotions of the broader community. Some reported that the sheer volume of distress—with the compounding impact of droughts, bushfires and COVID-19—meant that it was more challenging to rely on their usual coping strategies. Suggestions from consumers on effective programs during COVID-19 included lower-intensity online support or opportunities for social connection, such as peer support telephone and online programs.

The National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan identified as one of its 10 priorities addressing the complex needs of those living with mental illness by promoting best-practice care. This includes assertively providing outreach for those who are in crisis, including suicide crisis, or have disengaged from their services; increased community-based services, thereby reducing emergency department presentations and reliance on inpatient services; and physical health screening for people who had a pre-existing mental health issue and were treated for COVID-19 in hospital.

People with disability

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability published a Statement of Concern in March 2020 and a report in November 2020 on findings of the experiences of people with disability during COVID-19. The report was critical of the Australian Government for not engaging with the disability sector earlier in the pandemic. It highlighted evidence of a number of barriers faced by people with disability during COVID-19 and that many experienced:

- • stress and anxiety related to fear of contracting COVID-19 because of exposure to different support staff

- • distress, particularly among people with cognitive disability, due to the lack of clear and consistent information about the pandemic and the measures taken to control it

- • a sense of being forgotten and ignored, particularly when isolated from family, friends and social networks.

The report made 22 recommendations, including involvement of disability representatives in all future planning for natural disasters and emergencies, and establishment of a dedicated unit within the Australian Government Department of Health to plan for the safety and wellbeing of people with disability during these events.

A Disability Information Helpline, the Disability Gateway, was established for people with disability, and their families and carers, who need information that is free, private and fact checked for COVID-19-related assistance. The Australian Government Department of Health also established a COVID-19 Health Professionals Disability Advisory Service telephone line to provide specialised advice for health professionals involved in the care of people with disability diagnosed with COVID-19 or experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

In April 2020, the Australian Government announced the development of a Management and Operational Plan for People with Disability, which would form part of the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). The plan is intended to ensure that the healthcare needs of people with disability, and their families and carers are met during the pandemic, and emphasises the need for continuity of quality mental health care. Although the plan has been welcomed, criticisms have arisen that it should have been prioritised earlier, because of the additional risks to people with disability

The National Disability Insurance Agency has been consulting widely with providers and other key stakeholders to understand the issues that have arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic. For participants with psychosocial disability, key concerns include the difficulties faced in moving to telehealth approaches for service delivery.

The Australian COVID-19 Vaccination Policy includes disability support workers and people at higher risk of infection as priority groups for vaccination. It also includes a commitment that all Australian Government and state and territory governments will consider the needs of residential aged care and residential disability settings.

Young people

Evidence that more than 75% of mental health issues develop before the age of 25 highlights the need to ensure that young people experiencing mental distress as a result of COVID-19 receive access to timely support and treatment. An annual youth survey by Mission Australia noted that young people identified the most important issues in Australia as equity and discrimination (40.2%), COVID-19 (38.8%) and mental health (30.6%). Findings from headspace’s 2020 National Youth Mental Health Survey of 3,575 people aged 12–25 indicate that three-quarters of participants reported that their mental health was a little worse (47%) or a lot worse (27%) since the outbreak of COVID-19. Psychological distress is high, with one in three reporting high to very high levels of distress; an increase of about ten percentage points was seen since 2018 for young men aged 15–17.

Young people’s education has been significantly disrupted during the pandemic. Those transitioning from school at this time are at particular risk of increased stress, depression, isolation and use of unhealthy coping mechanisms.

The National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan identified the need for educational responses, including long-term education supports for students who may have fallen behind in their learning or disengaged with education, to get them back on track.

Year 12 students of 2020 also faced a historically unprecedented challenge as disruption to their year affected many school milestones. These impacts include disruptions to study, ‘Schoolies’ and formals being cancelled, gap years being abandoned and youth unemployment reaching almost 13.9%.

The impacts of COVID-19 on international students are addressed in the National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan. These students face new challenges relating to travel restrictions, study implications and visa concerns. These are in addition to longstanding challenges, including being away from traditional family supports, adapting to a different culture, financial stresses, study pressures and loneliness.

The Australian Government made a commitment of $509 million in the 2019–20 Budget towards the Youth Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, including expansion of the national headspace network, tailored initiatives with a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, and investment in early childhood and parenting support.

Regional and remote communities

At the time the pandemic was declared, many rural communities were coming to terms with the long-term stress, and social and economic impacts, of years of drought, and the recent devastating bushfires. Thirty per cent of the Australian population live in rural and remote areas. These people often have poorer health outcomes due to their geographic isolation, lifestyle differences, and a level of disadvantage related to education and employment opportunities, and poorer access to health services, especially mental health services. Frequently, mental health care in rural and remote communities is provided through community health centres, hospitals in major regional centres and a small number of GPs.

Many communities have no resident mental health services and must rely on visiting services, or travel to communities where services are available. People requiring services often have to travel away from their families and communities, which becomes an additional stressor and denies them an important source of social support.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this travel was even more restricted. For many remote communities, such as remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia that rely heavily on fly-in fly-out (FIFO) services, the strict and multilayered travel restrictions resulted in significant practical, administrative and financial challenges to local service provision. For example, although mental health services were covered by exemptions allowing the entry of essential services, FIFO staff had to be provided with accommodation and allowances while in quarantine, often in private accommodation; costs were often higher as a result of inadequate quantities and qualities of staff housing in some communities. As a result, many Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services were paying for staff yet unable to work to full capacity, making it even more difficult for communities to access mental health support when it was most needed.

The development and implementation of new technologies such as telehealth (see Box 11 for data on telehealth use) that overcome issues of distance and isolation have been essential in providing continuing mental health care for rural and remote communities. Internet technologies also enable opportunities to provide information about mental health and mental distress, and to connect people living in rural and remote communities with support groups.

Refugee and migrant communities

The need for all communities to access clear public health information is crucial during a pandemic. It is not enough to just provide translated information: governments need to ensure that the meaning and intent, especially for government announcements in relation to COVID-19, are clear and accessible. The National COVID-19 Health and Research Advisory Committee, in its report on risks of a resurgence of COVID-19, indicated that migrants may experience particular barriers to infection control, such as not understanding that testing is free, not having access to all available information in their language, past medical trauma and wariness of government, and labour exploitation limiting access to health care (such as a lack of sick leave).

In April 2020, the National Refugee-led Advisory and Advocacy Group held national community consultations on COVID-19.

For many groups within the refugee community, closing the digital divide to enable equitable access to online resources and services was reported as an issue. Digital literacy and costs of digital platforms could also be challenges for home schooling and online learning for refugee children and youth, and their parents.

The consultation noted the importance of community safety and wellbeing during the pandemic—misinformation and panic had been seen in refugee communities due to inadequate, decentralised and limited translated audiovisual information.

Stories of communities coming together to support each other emerged as a reminder that, given the opportunity and resources, affected communities can devise the most effective and efficient solutions to their own challenges.

Charities that support refugees and asylum seekers have called for the Australian Government to extend income support payments to these groups as they see increases in demand for assistance in their communities. Temporary visa holders have not been eligible for income support, such as the Australian Government JobSeeker and JobKeeper payments. This has left many people without income during the restrictions, as casual positions have decreased and businesses have closed. This loss of income has placed many in financial stress and led to concern about their temporary status.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer people

Social isolation can significantly add to existing mental health issues for young LGBTIQ+ people. Without the support of friends and the school environment during lockdown, those who are experiencing tensions in the home may find that these intensify, increasing the risk of mental illness. In response to COVID-19, the MindOUT project, a suicide prevention initiative, has provided PHNs with access to an existing online module - introductory lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and intersex mental health and suicide prevention training.

Rainbow Health Victoria recommended the sharing of messages about community resilience and increased initiatives to provide community support through adaptive means. Consistent with the broader population, connection to community and peer support have an important protective effect for LGBTIQ+ people.